Eddie Bauer, JCPenney, Wrangler—these are the labels you’ll see in the New-York Historical Society’s latest exhibition, “Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of Women’s Dress, The Smith College Historical Costume Collection,” which opens today. But in fact, most of the works on display have no labels at all. Let’s not forget that most women’s clothing throughout history has come not from fashion houses but from home sewers or local seamstresses. This is not an exhibition celebrating rare and exquisite relics of clothing history, but a celebration of everyday clothing for American women—a fashion category often ignored by fashion media and academia. We may already be familiar with the Dior gowns worn to ceremonies by the swans of high society in the 1950s, but what did pregnant women of that era wear while working at McDonald’s? The show features just her exact uniform; it’s a navy blue tunic and pants embroidered with golden arches on the chest—Moschino, enjoy it.

Anna Danziger Halperin, associate director of the Women’s History Center at the New York Museum of History, said: “Every thread and length of fabric displayed in this exhibition offers a fascinating account of the women who wore these garments. Profound clues. She curated the exhibition with Keren Ben-Horin, a curatorial scholar at the Women’s History Center at the New York Museum of History, which is organized into five themes: clothing for domestic work, clothing for service work, social wear, clothing reflecting a woman’s rite of passage, and ultimately, clothing that broke gender boundaries.

The Smith College Historic Clothing Collection was founded by costume design professor Kiki Smith, who led the collection of more than 4,000 items of clothing and accessories and scholarly research, the New-York Historical Society’s exhibition complements these objects with her works. In addition, the exhibition includes a rich background of primary sources (photographs, advertisements), making the exhibition a user-friendly exhibition of 30 works.

“Real Clothes, Real Lives” begins with a handmade printed cotton with a subtle black and white floral pattern, approx. 100 cm. 1865-1870. The garment is displayed on a mannequin, with additional information provided on the plexiglass surrounding the garment. Through these exhibition clues, we discover that the loose sleeves of the dress were not due to a lack of sewing ability, but to allow the wearer to roll up the sleeves. A nearby photograph of textile mill workers at the time shows what the scene was like. Additional information is provided by the colour of the garment, which suggests the wearer was in a state of mourning, while interior garment photography reveals that the garment was lined with a variety of fabrics, revealing that the maker was literally faceless, and how at some points the garment could adapt to the changing shape of the body. If a photograph can tell a thousand stories, a dress can do the same.

The fluctuation of the body is part of the female experience and is another thread that runs throughout the exhibition. Many of the costumes on display, including the aforementioned McDonald’s uniform, were made specifically for or adapted for pregnant women. Browsing the exhibition, we see the modest but visually appealing domestic garments of women in the 19th and 1940s transform into a sexy housecoat known as the “slenderall”, a skirt and apron set that could make housewives look attractive even while vacuuming. Well-made nursing uniforms show how the medical profession became acceptable to upper class society, while bifurcated bicycle uniforms, with modesty panels covering the wearer’s legs, exemplify the century’s demand for female modesty.

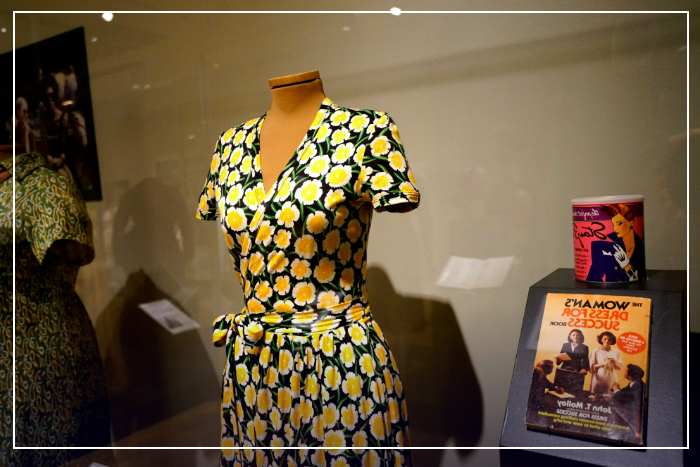

The show concludes with clothes that brought women into the modern, independent era. A Diane von Furstenberg wrap dress (the only “designer” in the group) stands next to a yellow micromini dress designed by a college student in the late 1960s, handmade by first-graders—the kind that inspires youthquakes.

Although the exhibition lacked the technical extravagance of a typical fashion show, it was still a fashion show in every sense of the word. These clothes are where we come from – they need to play a role beyond looking good because the women who wear them have the same expectations. Despite the merits of fiction in fashion scholarship, reality tells a better story.