If there’s one brand in the fashion world that’s both ubiquitous and obscure, it’s master mannequin maker Stockmann.

They are numerous and found throughout the industry, becoming permanent fixtures in shop windows, studios, showrooms and wardrobes. With their light padding, beige cotton exterior and standardised size (for a classic model anyway), they are deliberately innocuous, almost to the point of going unnoticed. A blank slate, but with a human dimension.

From luxury brands to fashion schools, retailers to museums, they are the model of choice. Dior, Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Celine, Rabanne, Prada, Loro Piana and many other brands are dedicated to creating stock sewing garments to adorn and grace the mannequins that walk the catwalk. Maison Martin Margiela even designed a collection around them in 1997 and, as seen at Vetements this afternoon, they are once again a source of inspiration. While Stockmann is more discreet than the bold font on the hoodie, Stockmann’s distinctive typographic branding – either under the collar or just below the hip – predates the rise of luxury logos. In a way, the name has become synonymous with all things mannequins – a coveted commodity in the same way as Kleenex.

Today, like the papier-mâché fashion models that appeared in 1867, they too are handmade in France. This is one of the many reasons why they are still so respected. They represent the level of detail and craftsmanship found in haute couture (that rarefied realm of fashion where customers have a mannequin made exactly to their own measurements).

At the beginning of the summer, I got a surprise invitation to visit their headquarters. Any behind-the-scenes tour is a privilege. After all, I first learned about the hustle and bustle while spending time in the studio. It’s a chance to peek into the other corner of the fashion machine.

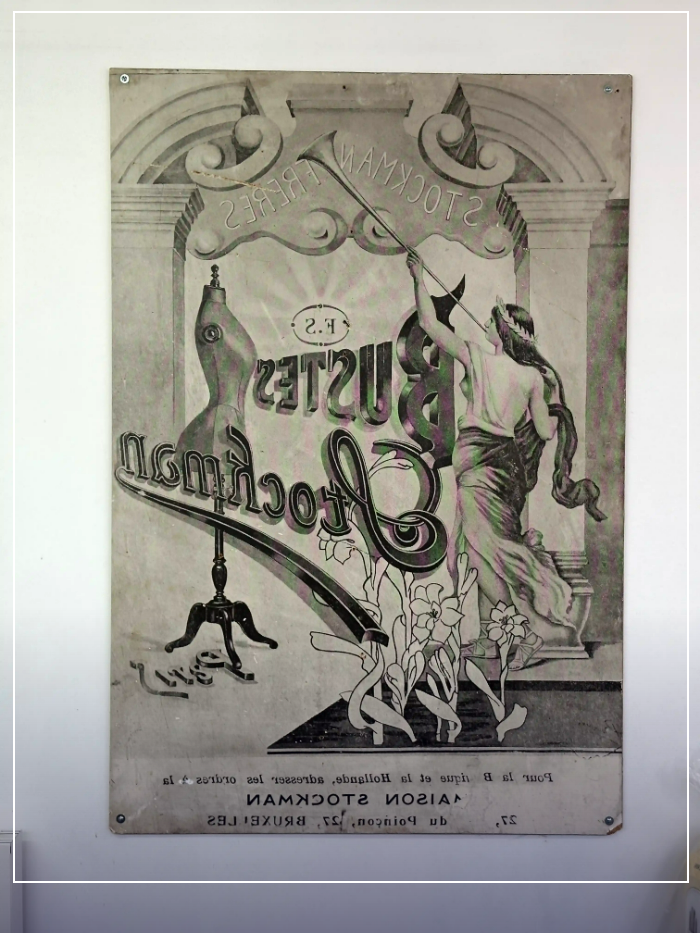

The Stockmann workshop is located in the Paris suburb of Genvilliers. It is small in size and very simple in appearance. The office area lacks any of the amenities of the company’s luxury clients, except for the arrangement of framed fonts, which have been adapted for some homes.

Louis-Michel Decq, Stockmann’s general manager since 2018, uses male busts as coat racks. He provides some stats about them before the journey begins. They make about 30,000 busts per year, depending on the year. While the B306 is their classic product, its look has evolved as the company measures it based on size surveys conducted every 10 years. When the results come in, they do “inventory management” or optimization. Then there’s 50463, known for its cameo in the 2021 film Cruella. The shapes of these mannequins look similar, but they come in different sizes – usually 2 to 10, but up to 60 for women.

Stockmann has been a successful business since the Second Empire, when fashion designers such as Charles Frederick Worth opened salons throughout Paris and sculptor Frederick Stockmann learned to make Italian tailor dummies out of paper mache. The company changed its name to Stockmann & Siegel in 1900 (merging with another mannequin maker) and continued to offer studios and shops until a defining moment in 1947: the creation of tailor-made models based on Christian Dior’s “New Look” modeling.

In 2012, Stockmann & Siegel received the title of Enterprise de Patrimoine Vivant, a label awarded by the state to companies protecting living heritage. The current owner, Christophe Israel, lives in Marseille, where there is another factory. The business remains family-owned, with offices and showrooms in New York.

Eventually we make our way through the cobbled courtyard of the headquarters into the warehouse-cum-workshop complex where dozens of sculptures under protective plastic covers immediately attract attention. Excluding custom orders, there are about 200 different molds available to match the shape and dimensions.

Deck leads me to a workstation where Carlos, a skilled craftsman who assembles and sculpts figures, is preparing a custom mannequin for one of the houses mentioned above. While a high-fashion bust like B406 can be produced in 72 hours, a fully customized mannequin can take up to three months to create. Precision is the essence of the work. But then came the surprise – it seemed as though the size of the haute couture bust would change as the bride’s wedding approached.

Next to it is a sculpture of a particularly fat man, covered in a kind of embroidered velvet panel. It was made in 2002 to the proportions of Pavarotti. There are countless more stories hidden within these anonymous forms.

Nearby is the pulping station. The familiar smell of glue reminds me of elementary school art class, but over time, part of Deck’s mission is to reduce solvents and other petroleum-derived products. Needless to say, whoever laid out each strip of recycled paper learned to be extremely precise. “You have to be really good at using collage; you need to work hard to get it right,” Dirks said. The neck or waist can stretch a fraction of a millimeter, and the mannequin suddenly loses the accuracy of its proportions. “Every day, you’re conscious of all those points.”

Meanwhile, a worker named Maddie, whose muscular physique is evidence of her physically intense role, demonstrates how to remove the bust from its mold after it has been baked in a large oven for 10 to 12 hours. They used a drill, then a scalpel-like cutter and finally pierced its hard shell with their hand and split it in half.

On the upper floor, the chef oversees the stuffing and covering of mannequins with organic cotton or linen lining – again reflecting Deck’s more eco-friendly and attractive ambitions. Scrap materials are reused and packaging is now considered sustainably. All this happens in a workshop staffed by no more than 30 people.

Not surprisingly, Stockmann also offers a line of relatively easy-to-use fiberglass mannequins, which are used more for display purposes when dressmakers don’t need layers of padding. However, these are also covered with signature fabric unless the customer requests a new print or color. Yes, warehouse managers almost always have inventory on hand. Dyke said they get requests for a few of these mannequins, sometimes at the last minute when a brand or other decides to host an event.

“Six years ago, when I started in this position, I said, ‘We have to be creative, innovative and innovative in all areas, including business,’” he said, adding that the most valuable part of his work is that even though industrialization seemed inevitable, we still maintained our efficiency while being efficient. “We are always working hard to increase the quality of our craftsmanship.”

Alexandre Samson, who heads the haute couture and contemporary manufacturing department at Palazzo Galliera, explains that the museum loved Stockmann’s look for exactly this reason. “We use them to create vintage objects, or display them individually (without any accessories or stockings) or as independent sculptures,” he says. Having co-curated the “Margiela/Gallera 1989-2009” exhibition, he says that Margiela’s preference for showing the stages of dress construction at the time was prescient.

As I was returning to central Paris, I passed a shop displaying bare-chested jewellery. The brand around the neck now looks just like a necklace. There is a cognitive bias called the frequency illusion, where once you become aware of something, you start seeing it everywhere. With a little intention, I would probably now call it Stockmann syndrome.