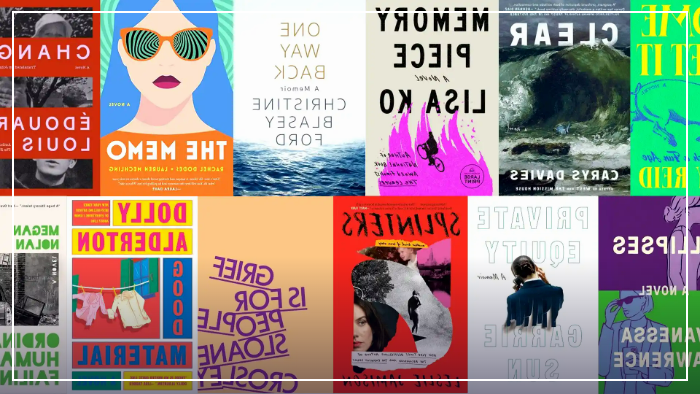

We like to think of this list of the best books of 2024 as an inverse algorithm, a collection of highly specific, highly personal and eclectic works that pique our interest and excite us, or genuinely impress us. At a time when curation is in danger of being overshadowed by cookies tracking your cursor and clicks, we hope this list and others like it will serve as a counterweight to that.

However, there should be a (little?) moderation in reading: we read a lot, but we can’t read everything! While one editor may favor crime fiction, another reads everything with a romance flavor. The danger of curating is that it is an act of inclusion and exclusion. (See the New York Times’ selection of the 100 best books of the 21st century and the almost immediate reaction it generated.) There are a lot of books, so we will be reading and updating them throughout the year – for our opinion on the best great books of the year, please check back at the end of the year!

Sugar, Baby, Celine St. Clair (January)

Celine St. Clair’s debut novel Sugar, Baby (Bloomsbury) depicts the glamorous world of young women who visit clubs and restaurants to demonstrate their attachment to youth and beauty. Are these women being taken advantage of or are their lives in jeopardy? This charming novel describes the uncanny journey of a girl who finds herself trapped among more familiar models, and to its credit, it doesn’t fall on one side of the equation. Instead, it displays charm and grit, tells a very believable story, and feels as if it’s documenting a moment when images were a precious and fleeting currency. -Chloe Sharma

“Come On, Get It” by Kelly Reid (January)

Another study of class and wealth appears in Come and Get It (Putnam) by Kiley Reid. Set on a college campus, the novel features a multi-threaded narrative filled with choruses, depicting a group of students, professors, and administrators at the University of Arkansas. The novel reveals that campuses are not only centers of academic inquiry and nighttime mishaps, but also crossroads of people with very different resources. Reid’s first novel explores the sometimes fraught relationship between a nanny and a single mother, deftly capturing the quiet dissonance that arises from the differing perceptions of what is at stake. It is a somewhat old-fashioned novel of manners, but deeply reflective of the modern moment. -C.S.

Good Stuff by Dolly Alderton (January).

Dolly Alderton is a modern Nora Ephron, bringing a refreshing and poignant perspective to the eternal struggle between the sexes. Her previous novel, Ghosts, used the mysterious male psyche as the narrator’s painful subject. Her new novel, Good Material (Knopf), tells the story of a breakup from the perspective of a tortured male. The story’s narrator, Andy, is a 35-year-old London comedian who, after several years of dating, has recently been dumped by his more corporate-minded girlfriend and must redefine his place in the relationship. She knows instinctively (if not from the perspective of her love-struck state) that — as Ephron might say — everything is a parody, and the book manages to find the funny in the angle of even the most poignant moments. —CS

Private Equity (February) by Cary Sun

Carrie Sun is a talented individual who, in the past, might have been selected for a prestigious doctoral program or sent to the CIA for covert training. The equivalent of being the personal and professional assistant to the highly successful CEO of a private equity fund is what Sun describes in his memoir, Private Equity (Penguin Press). At age 29, he thought the opportunity was more promising than the path he had chosen as a financial analyst, but the position’s enormous responsibilities soon began to overwhelm him. Sun provides a candid account of the job’s demands and privileges, and though it doesn’t address all of the industry’s shortcomings, it offers an in-depth look at what we consider success and the values behind it. —CS

Grief is for People, Sloane Crosley (February)

Within a few months, Sloan Crosley’s apartment was burglarized and her best friend was murdered. This coincidence forms the basis for a stunning investigation into the nature of loss, Grief Is Human (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), an ambitious book that brims with acerbic humor. Crosley, perhaps best known for her brilliant essay collection “I Was Told There’d Be Cake,” is not abandoning her playful wit, but she is moving toward a more critical look at what’s important here. The bizarre mission of recovering the stolen jewelry is juxtaposed with the equally insurmountable task of learning more about her lost friend, a well-known figure in the publishing industry. Crosley’s loving and complex tribute to him here will undoubtedly be bitter consolation for many. —C.S.

“Fragments: Another Love Story” by Leslie Jamison (February)

Leslie Jamison’s autobiography Split: A Different Kind of Love Story (Little, Brown) tells the story of the end of her marriage, but it’s also about motherhood and how life-changing events can change a woman. It feels as if a part of it has been broken off. Known and beloved for her assertive voice and unshakable convictions, Jamison has not shied away from self-introspection in the past, but her new book is a particularly poignant account of her own decisions, motivations, and desires. It’s also a remarkable book, taking the reader through exciting, painful, and gratifying experiences. —C.S.

Ordinary Human Failures, Megan Nolan (February)

Ordinary Human Failures (Little, Brown) is set in the 1990s, a remote area without cell phones, yet far enough away to offer instant multiculturalism through improved connectivity perspective. The Green family is at the center of Megan Nolan’s gripping new novel. They lived a secluded life on a London housing estate, before haphazardly fleeing to Ireland after their daughter Carmel became pregnant. Tom follows this unhappy family as a hungry young tabloid reporter who truly feels the wrongdoing that the Greens’ readers hate. In her careful and caring novel, Nolan shows how misfortune begins with a few bad decisions and how guilt becomes entangled with providence and privilege. Her prose is concise and precise; this is a book full of wisdom, but also consoling in its precise generosity. — C.S.

Baby Mama: A Novel by Katya Apekina (March)

Katya Apekina begins her role as Doll Mama (Abrams) in a moment of despair. Xenia, a failed actress who works as a medical translator, finds herself unexpectedly pregnant with a baby her husband clearly doesn’t want to keep, while her beloved grandmother slowly dies thousands of miles away. So when our hapless protagonist gets a call from a stranger named Paul, a psychic who claims to have contacted his Aunt Irina, a female Russian revolutionary seeking liberation, he agrees to hitch a ride. Apekina deftly weaves a tale of how the karma of our long-gone ancestors gets passed down to the next generation. “Dollmother” is a formal experimental work that presents the story of America from the Russian Revolution to the early Obama years with a Greek chorus of sad and talkative Russian ghosts. Apekina’s novel is not only a haunting look at generational trauma, but also a lot of fun. Filled with sex, revolution, spiritualism, and the occasional appearance of major Russian historical figures, Baby Mother is a gripping story from the first sentence. ——Hannah Jackson

The Way Back, Christine Blasey Ford (March)

Christine Blasey Ford’s highly anticipated memoir “The Return” (St. Martin’s Press) describes a time in her life when the scientist’s name was plastered on T-shirts across America, then she won the trust of women for the Me Too movement and she became a normal kid. Attack. Today, given the open politicization of the court, it can be a little hard to remember a time when such nominations seemed extremely important, but this memoir will take you there. It also paints a picture of the woman behind the complex calculations, presented with subtle and introspective insight. -C.S.

Change (March) by Édouard Louis.

“The Change” (Farrard, Straus and Giroux), written by French author Edouard Louis (“The End of Eddy, Who Killed My Father”), is an autobiographical novel that reads like the confessions of a madman: Eddy Bellecourt, Louis, from the north of France. What’s so disturbing? Lewis’s prose style is straightforward, translated into English by John Lambert; it’s full of self-aware observations and irregular structures with rapid shifts in form and an unflinching look at poverty and extreme privilege in modern France (if you squint, this is true elsewhere as well); showing a desire for better, different, more, but that this desire can no longer be reasonably satisfied. Here, self-invention is an act of brutal violence in which no one apparently survives. ——Marie Marius

Memoirs of Corissa (March)

Lisa Ko’s “Riverhead,” the follow-up to the 2017 National Book Award finalist “Leavers,” is an intense and engaging look at New York’s arts, tech and activist scenes over the decades. The novel tells the coming-of-age story of three friends who frequent a suburban New Jersey mall as they make their way in a rapidly changing world. They are troubled by their identities as Asian American women and resist the stifling expectations of their immigrant parents, longing to escape the demands of race, gender and family while also hoping for a future that’s bigger than they could have imagined. —Lisa Huang Mabasco

The Oval by Vanessa Lawrence (March)

Vanessa Lawrence’s satirical debut novel Ellipses (Dutton) charts the course of a toxic and narcissistic master-student relationship. Lily, a 30-year-old magazine writer struggling in the decimated ecosystem of brand-name print media, becomes entangled in an unbalanced power dynamic with Billy, a brutally self-confident beauty CEO who spouts harsh words with his black thumb. Since the relationship is entirely text-based, Lily’s life hangs in the digital bondage of a requisite blue text bubble (the ellipsis of the novel’s title). They meet when Lily is covering a “disease-oriented event”—Alzheimer’s Unforgettable Night, and we accompany Lily through her roller coaster of self-doubt and eventual self-actualization against the backdrop of the rise of digital media. Lawrence, who has written for W and WWD for more than two decades, uses her inner talent to artfully describe the microaggressions of office politics, like a neo-baby influencer turned vegan caterer. —Chloe Mahler

Asking for Help (March) by Adele Waldman.

Adele Waldman’s fast-paced novel “The Help” (Norton) is based in an upstate New York box store of declining fortunes, a setting that proves a welcome addition to Waldman’s steady hands’ examination of ambition and survival. “We’re With the Movement” is the company’s name for the employees who arrive at 4 a.m. to unload trucks full of household goods and drive them to retail stores. Waldman is not snobbish about her low-paid heroes, imbuing them with everyday heroism and vulnerability, and she’s drawn to the details of their work, the mechanical belting, the “throwing” of boxes and the meticulous unpacking. In one paragraph, there’s a thrilling specificity about the difficulty of taking off a bra. The engine of the novel’s suspense lies in their boss, Meredith, a narrow-minded and insensitive man who is a middle manager and whose team believes they need a promotion to beat him. ——Tyler Antrim

Real Americans: A Novel by Rachel Khong (April)

Following 2017’s critically acclaimed Goodbye, Vitamins, Rachel Khong’s Knopf tells the story of three generations of a Chinese-American family. This ambitious novel travels through cities across Asia and America over more than half a century, as decisions made in Mao Zedong’s China spill over into millennial New York City and the rural Pacific Northwest today. Along the way, with a touch of magical realism, it considers fate, race, and privilege as the three protagonists confront how their lives have been shaped by biology, world events, parental choices, and sheer luck. The novel ultimately emphasizes the difficult task of escaping a predetermined fate. —LWM

Boundaries by Nell Freudenberger (April)

In Nell Freudenberger’s busy and intelligent fourth novel, “Extreme” (Knopf), the story stretches from Tahiti to East Hampton, charting the course of strange desires and teenage neurosis. French marine biologist Nathalie is studying the harmful effects of climate on corals in French Polynesia. Her ex-husband, Stéphane, is a Manhattan cardiologist who contracted the coronavirus and recently married Kate, who is pregnant and uncomfortable with Stéphane’s opulent lifestyle. Connecting the two worlds is Pia, Nathalie and Stéphane’s 15-year-old daughter, who moved to New York from Tahiti to enroll in high school and longs to connect with someone but doesn’t know how. Pia’s passionate resentment in Freudenberg’s worldly and complex story is where the essentially good characters make mistakes and misfortunes wherever they go.

Clarity (April) by Caris Davis.

On a remote island off the coast of Scotland, a lonely tenant — cut off from 19th-century society because of the distance and his rare dialect — is preventing the landlord from converting the property to a more profitable use. Hire a minister to convince the tenants to leave the house. But soon after arriving on the island, he suffers a terrible accident and is forced to recover in the care of the man he had banished. This unique premise is the backdrop for Wellesian novelist Carys Davies’ surprisingly entertaining novel Clear (Scribner), which feels like a history lesson brought to life brilliantly. Eventually, the pastor’s wife travels to the remote island in search of her husband, and her arrival disrupts the previously existing intimacy between lodger and pastor, revealing how belonging, ownership, and true and lasting connections between our people and places are built on it. —C.S.

“On the Tobacco Coast” (April) by Christopher Tilghman

A faded estate on Maryland’s Chesapeake coast, filled with families spending the Fourth of July weekend together and haunted by its history, is the setting for Christopher Tillman’s elegant, hilarious and poignant new novel, “The Tobacco Coast” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). The backdrop. Mason Retreat is the name of this farm and ancestral home, dotted in haute WASP style with salty marsh air, oyster shells and drawers full of mismatched cutlery. Tillman has now written four critically acclaimed novels based on this landscape, exploring rich themes of race, class and privilege. “The Tobacco Coast” is the first story set in the present day and features believable characters: Kate and Harry, the owners with their three grown children struggling with differences with their peers; a pair of French cousins; a group of elderly neighbors. Tillman expanded through them — the inner lives of her Vassar classmates were as much hers as the inner life of the 96-year-old Chesapeake woman — as they gathered for a wonderful dinner, hidden conflicts and great pains inevitably intertwining with the formality. —TA

Double Exposure: America’s Most Enigmatic War Photographer, Timothy Sullivan, Revisiting the West with Robert Sullivan (April)

Written by a longtime Askew contributor and ostensibly about the later work of Civil War photographer Timothy O’Sullivan, this unique book is not a biography, either in the traditional sense or any other, nor a study, nor an argument. Yes, Sullivan was trying to portray “what was going on” in O’Sullivan’s photographs – the double exposures (Farrard, Straus and Giroux) during which they emerged like his Rosebud or Rose Tower Stone – while also exploring fundamental assumptions about what one should look like. The wonder of this book, however, is in its DNA: it is an investigation in the most wonderful sense of the word – a disorienting, controversial, road-trip eccentricity that seeks us out amid hostile perceptions of the American West. Lost battlefields still littered with wounds, warning signs, curses and signs of conflict. But Sullivan is in this book – his ideas and theories; His wild and sometimes terrifying personal stories, offbeat conversations, dry humor, and, best of all, his perspective on the nature, clever presentation of the various clues in the world he seeks, stumbles upon, misses, and puzzles out – these are what make this book inspiring, offering its own poignancy and local beauty. Double Exposure is the best book written about America in the last few years – its history, lies, missed opportunities, miracles, madness, innocence, and glory. – Corey Seymour

The Butcher: A Novel by Joyce Carol Oates (May)

This interesting historical novel could have been considered incomprehensible because of its subject matter – it’s about a deranged 19th-century gynecologist – if it weren’t in the hands of such a capable reader. Joyce Carol Oates – 86! As always, her story is based on historical fact: a disgraced Pennsylvania doctor named Silas Aloysius Weir was appointed to a New Jersey asylum for female lunatics, where he began receiving experimental treatments that he was convinced he had to undergo. His actions against the poor women of the asylum were motivated by selfish utilitarianism and creepy perversion – resulting in a violent uprising. Oates is sympathetic to her character and doesn’t hide any of the horrors in the story, she describes Will’s experiments with a matter-of-fact calm that heightens the horror. This would be a brilliant story if it weren’t for the faint of heart. -TA

Exhibition: Ro Kwon’s Novels (May)

“Exhibit” (Riverhead), the follow-up novel to Ro Kwon’s 2018 bestseller “Burner,” is a provocative tale of female desire that follows three Korean women as they seek artistic, sexual and personal freedom outside the dictates of society: Jin, a photographer at a crossroads between her job and her marriage to her beloved husband Lidija, the injured world-class ballet dancer who is stalked and the ghost of a prostitute whose curse may be caused by the golden man; plagued by encroaching desires, they must work to overcome the barriers of religion, family and history before finally confronting how far they will go and what they will sacrifice to achieve the lives they want. Yes, it’s about sex, but it’s also about the desire to embrace and honor the body and the freedom for creativity to flow freely without restraint. -LWM

On All Fours, Miranda July (May)

Miranda July’s “Riverhead” begins with a funny and quirky story about a 40-year-old creative woman from Los Angeles – semi-famous, married, and… kids, between projects – in search of her story (she embarks on a two-week drive across the United States to prove to her husband that she can take risks. About 15 minutes from the city center, she parks her car at a seedy motel, embarks on a different journey while talking about sex, interior design and periods of self-sacrifice. It’s a candid novel about midlife awakening that’s funnier and more daring than you’d imagine—evidence of a classy, stylish eccentric who is no less daring.

Anxiety (March) Alexandra Tanner

Jules, 28, juggles her personal and professional life simultaneously, her stagnant relationship and post-MFA aspirations reflected on her Mormon Mom blog account. Jules is rudely awakened when her sister, Poppy, suddenly moves to New York and half-heartedly sets out to look for an apartment. “Anxiety” (Simon & Schuster) is a chaotic and extremely funny portrait of two neurotic sisters who find their relationship on the verge of collapse when they become roommates. Set after the 2016 election and before COVID-19, Tanner captures the spirit of the late 2010s — from pyramid schemes to a dog named Amy Klobuchar — without seeming stale, dominating them. Angst is a pressure cooker of sisterly stories mixed with mommy problems and plenty of Jewish humor. —HJ

Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk, by Kathleen Hanna (May)

Kathleen Hanna may not be a well-known name in mainstream American music, but she’s been a well-known figure in the alternative music scene for the past 30 years, first with Bikini Kill, a band from Olympia, Washington, in the ’90s. She was a feminist punk band (she coined the term “riot grrrl”) and later became the lead singer of the electro-pop band Le Tigre, whose songs are danceable and politically driven. In her memoir, Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk (Echo), Hanna gives some details about her tough upbringing, the early days of her band, and the group of other musicians she surrounded herself with. (“The smell of teen spirit” is the line she wrote on Kurt Cobain’s wall one night.) Together, the stories paint a portrait of a young woman trying to navigate a sexist culture while finding her creative voice. Likewise, it is believed that “Rebel Girl” was written as a road map for a new generation to pick up their own devices and shake up the world. -Raye Garcia-Furtado

Women and Children First by Elena Grabowski (May)

Women and Children First (SJP Lit) by Elena Grabowski is a novel made up of interconnected stories, each chapter of which begins from the perspective of a different woman living in a small coastal town in New England. In less capable hands, such rapid changes could have had a confusing effect, but the book weaves an engaging web of stories that reflect the spirit and subtlety of Mary Gaitskill, who effectively captures as much information as possible about the town’s residents. They include a lonely teen who had an affair with a school teacher; a PTA president whose overbearing energy was a distraction from the chaos in her home; and the mother of a local teen who died unexpectedly; the cause of death is the mystery of the title of ‘Women and Children First,’ but this book is about the secrets we keep hidden and the lies we tell to hide from each other. -CS

“The Winner” by Teddy Wayne (May)

The story of Teddy Wayne’s “The Winner” (Harper) is charming: A beautiful, young tennis teacher and recent law school graduate moves to a small town on the coast of Massachusetts, where some masters await during the universe pandemic. He’s given a guest cabin in exchange for on-demand coaching. However, tennis is only part of the deal. Immediately seduced by a crazy resident, he develops a mutually beneficial but extremely interesting relationship with an older woman, while slowly falling in love with her daughter – something both women want. Law is unaware of her existence. After writing so many novels that put the pandemic front and center, it’s comforting to read some material that features it as a plot – creating a page-turning story about sex, power and money relief. -CS

“The History of a Strange Event” by Claire Messud (May)

Claire Messud has turned the story of three generations of her family into a stunning tale in A History of Strange Events (W.W. Norton & Co.). Spanning 70 years, this novel is both ambitious and intimate, and is Messud’s best since 2006’s The Emperor’s Children, which traced the history of black people displaced by Algerian independence as she traveled around the world, stopping in France, Canada, Argentina, Australia, and the United States. The turmoil of the 20th century was all around her, but although Messud was creating a grand canvas, her technique was only a microcosm. The History dazzles with its subtle character studies: François’s unmarried sister, trapped in a family apartment in Toulon, France, hiding the pain of losing her lover; François’s Canadian wife Bara; her two daughters (one of whom is charming and obnoxious; one is an aspiring novelist who later attains authorship); And many other characters and family members are beautifully introduced. This is a pointillist novel that deeply portrays tension, bonding, and heartbreak.

Wives Like Us by Plum Sykes (May).

Plum Sykes’s entertaining new novel “Wives Like Us” (HarperCollins) bears a striking resemblance to the nineteenth-century novels of Austen’s time, although what makes country gentlemen desirable now is not a ten-thousand-pound estate but an infinite amount of money. At the center of this satirical drama are goofy and lovable heroines, who are mostly paired together — but who can stop them from finding husband number two? Sykes combines the parameters of modern social influence (Instagram followers, bikini line startups, freewheeling glam teams) with the estates and stables of traditional Cotswold landscapes, and the result is a delightful combination. It depicts a social milieu that recognizes traditional values but is always looking for something new. —C.S.

Ask Me Again by Claire Sestanovich (June)

When Eva and Jamie met in an emergency room at age 16, neither had any idea how this chance encounter would shape each other’s lives over the years in “Ask Me Again” (Penguin Random House). In this anthropological excavation of a coming-of-age story, Claire Sestanovich juxtaposes Eva’s linear path with Jamie’s chaotic perspective. Ask Me Again is a sprawling novel filled with modern paradigms, from the Occupy movement to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s stand-in—all of which shape Eva and Jamie’s flexible world view. Sestanovich is a skilled and precise writer who isn’t afraid to ask life’s big questions, even—especially—when she doesn’t know the answers. —HJ

Godwin, by Joseph O’Neill (June)

Joseph O’Neill’s riveting 2008 novel Holland examines crisis and identity through the lens of cricket. Nearly 15 years later, in the entertaining Tramp Godwin (Pantheon), O’Neill takes another sport as his subject – football – and uses it to examine brotherhood, immigration and the late-capitalist striving that adds color to his story. The main character is an African boy who plays football in a village stadium and whose uncanny talent sparks a race to find and monetize him. Godwin, original and wild, features a ruthless future football scout and a scheming French sports agent, as well as protagonist Mark Wolfe, who joins the hunt after escaping a Pittsburgh technical writing co-operative filled with power struggles. -TA

Soldier Sailor, Claire Kilroy (June)

Claire Kilroy’s new motherhood story Soldier Sailor (Scribner) leaves a distinctly bleak impression, writing in a tone that mimics the amorphous nature of the dimensions of early parenting, at a time when the act of raising children was both exciting and mind-numbing. Kilroy’s novel tells the story of a soldier mother telling her sailor son. The child ended life as she knew it and she recreated it: as Sellers explains, something deeply connected with her. But the relationship also imprisoned her, and this book is an account of her losses and gains. Sellers’ father is a marginalized, almost cartoonishly incompetent figure who is also incredibly believable. There is a constant critique of gender roles in the book, but men are not entirely the enemy. In fact, it is a chance meeting with an old (male) friend that pulls the narrator out of her preoccupation and allows her to see and appreciate the beautiful contours of her life. -CS

Death in the Sky, Ram Murali (June)

Ram Murali’s debut novel, Death in the Air (HarperCollins), is set in a unique sanatorium in India that bears an uncanny resemblance to some of the high-end spas that claim regional expertise in traditional Ayurvedic principles, and the ways they put that knowledge to use. But this isn’t just a satire on health pilgrims (and the big businesses that serve them), it’s an old-fashioned mystery in the Agatha Christie mode. Murali’s characters, despite their glossy attachment to the material world, are hopelessly adrift. This is a mystical, funny, and genuinely escapist book—offering a level of perspective that feels both exaggerated and very real. —C.S.

Tehrangelis: A Novel by Porochista Khakpour (June)

Porochista Khakpour brings her unique voice to the long-in-progress Tehranjelas, a satire based on the epidemic that has been going on for nearly four decades as the daughters of immigrants growing up in McMansions in America build a microwavable snack empire. While shooting a reality show, each girl — even the family’s sly Persian cat, Angel — is hiding a secret that surveillance cameras throughout the show are threatening to expose. Think Kardashians meets “Little Women” and “Crazy Rich Asians”; the first page mentions Zodiac reenactments, Barbie ballet lessons, angel numbers and Cavalli Havana sunglasses. It’s an indelible, light-hearted snapshot of a young woman in a time most of us would like to forget. —LWM

“The Memo” (June) by Rachel Dodds and Lauren Mechling

Have you ever wondered if everyone else has somehow got their hands on some secret information, insider information, or just a map that helps them understand the overall state of the world? That’s the premise of Harper Perennial, Rachel Dodds and Lauren Mechling’s brilliant new novel. Down-on-her-luck heroine Jenny Green is struggling to find nonprofit work in a remote coastal town while her college classmates and co-workers are being promoted to more prestigious positions. Jenny doesn’t care where her life takes her, but she is plagued by a universal concern: what if? When a surprising (and somewhat supernatural) encounter causes her to relive parts of her life, she embarks on a wild adventure to find out what her life could have been like. Modern Sliding Doors is set in a very unique setting, a symbolic allegory with a very relevant heart. -CS

More please: On food, obesity, overeating, cravings and the desire for ‘enough’, by Emma Spector (July)

In this fascinating series of articles, Emma Spector reports extensively on her lifelong struggles with body image and overeating. Sure, the subject matter is intense, but don’t expect a boring read. More, (HarperCollins) is full of the sharp wit and dry humor that Spector often employs as a writer on eScum culture. This book is both funny and compassionate. As she looks at the stages of eating disorders, Spector is careful never to point a finger, instead exploring how our early lives shape our psyche. In addition to self-exploration, Spector generously gives readers space to think about their own food-related questions, which everyone can surely relate to in some way. -HJ

Somebody’s Ghost, August Thompson (July)

In his debut novel, Nobody’s Ghost (Penguin Press), August Thompson explores the complexities of childhood and adulthood, love and loss, music and silence. One summer in rural New England, fifteen-year-old Theron David Alden meets Jack, a boy two years older but more at ease with himself. Through glimpses of Andre Aciman and Donna Tartt, this book enchants from the first sentence: “It took three car accidents to kill Jack.” —Ian Malone

Whoever You Are, My Love, Olivia Gatewood (July)

For the past 10 years, Mitty has lived in a shabby bungalow in Santa Cruz with his old roommate, Bethel, and curses the tech boom for allowing wealthy startup founders to destroy their secluded beach community. But when one such inventor, Sebastian, and his girlfriend Lena move into the glass house next door, Mitty finds himself fascinated by the otherworldly woman he sees through the window. Through their new friendship, Mitty and Lena help each other, and sometimes force each other to confront inconvenient truths about their past. Wherever You Are, Darling is set against the backdrop of the murder of an artificial intelligence pioneer, the timeless heart of Gatewood’s first novel. Lucky Chap Productions has begun production on Margot Robbie’s “Whoever You Are, Darling,” and we won’t have to wait long to see how Gatewood’s vivid story plays out on screen. -HJ

Long Island Settlement: A Novel by Taffy Broderser-Akner (July)

Taffy Brodesser Akner’s sequel to the bestseller Fleishman Is in Trouble is another tale of modern neurosis, told with exaggerated appeal. In “The Long Island Compromise” (Random House), Brodesser-Akner has given herself a broad canvas, tied to the setting of a particular Long Island town in the 17th century, to flesh out the pathologies of one particular family. The Fletcher’s earned great wealth by manufacturing styrofoam (or, as she calls it, which is a better word) styrofoam, which (appropriately) alienated and poisoned the generation that inherited it. The three grandchildren of the factory’s immigrant founder are the extremely unpleasant heroes of this unfortunate tale, and you have to have a strong stomach to put up with all their pathetic rich-kid antics. But Brodesser-Akner’s patience and enthusiasm are remarkable. Philip Roth’s investigation of American Jewish identity, the promise of America, the euphoria of Reconstruction, and the echoes of the prison of privilege. I can’t think of any living writer better at crafting strong, poignant stories filled with compassion while also entertaining the reader. -C.S.

“Burning” by Peter Heller (August)

A charming isolationist? Peter Heller’s compelling and closely observed new novel “Bourne” (Knopf) is the story of two old friends on a hunting trip through the woods of northern Maine who stumble into a dramatic event. A town has burned to the ground. A nearby bridge has been blown up. Is there artillery fire in the distance? Without cell phone coverage, Jesse and Story must piece together the disturbing truth: They are in the middle of a daring negotiation between local militias that has grown more dangerous. As Heller showed in acclaimed novels such as “The Last Ranger” and “The River,” he was a literary novelist with a knack for suspense and a portrayal of the natural world that was unparalleled. A pot of campfire coffee in the barn is suddenly interrupted by a helicopter attack, and Jesse and Story’s fight to survive exposes all their human vulnerabilities — and the hidden truths that define their friendship. —TA

Tell Me Everything (September) Elizabeth Strout

Award-winning novelist Elizabeth Strout’s newest entertainment is as reliable as it’s ever been this season. Her ten interconnected novels take her readers back again and again to characters she’s created who are as indelible as old friends: Lucy Barton, a successful novelist with a painful past; Oliver ‧Olive Kitteridge, a tough miner in his 90s; and Bob Burgess, a lawyer with moral core and secret desires. They’re all in “Tell Me All,” a panoramic view of small-town Maine filled with suspense as a murder charge is brought against a local man and Bob takes the stand in her defense. Strout’s Hemingwayesque prose and her simple views of friendship, family and marriage rarely capture the intoxicating human joy of the show. Lucy and Oliver share stories about living in a nursing home; Lucy and Bob go for daily walks; and Bob’s brother and ex-wife grapple with the death of his wife, his son’s car accident and the recurrence of alcohol addiction. Somehow, they all found ways to connect, to accept, to endure their heartbreak. -TA

Colour TV by Danzy Sena (September)

Danzi Senna’s hilarious new novel Riverhead Mulatto follows Jane, a biracial writer working on war and peace, as she struggles to maintain the narrative of her family’s unstable, nomadic middle-class creative lifestyle. Seeking a more lucrative career, she turns to glossy Hollywood and teams up with a charming young producer to create a made-for-TV mixed-race comedy for a streaming network. Quirky and absurd, it explores the surreal interconnections of class, politics, art, motherhood, and the industrial complex of racial identity. -LWM

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner (September)

Some novelists have their own style, while others have styles that vary widely. Rachel Kushner falls into the latter category, writing this novel after her brilliant 2018 novel The Mars Room, which was partly set inside a women’s prison, narrated by an inmate. The new novel The Lake of Creation (Scribner) is set in a dusty backwater in the French countryside, where a charismatic leader Bruno Lacombe sets up a commune-like place where people (their identities remain mysterious) want to break it apart. Anyone who sees danger in this diverse counterculture team sends a woman named “Sadie” to infiltrate them. Sadie is a psychic who is so convinced of her deceptions that she seduces one of the leader’s childhood friends to get inside information. But as the plot progresses, questions of control and coercion, reality and idealism slowly emerge in Kushner’s noir novel. “Sadie” has unflinching confidence and a very detached approach – severing any loyalties or emotions before any kind of bond can be formed. But Kushner’s story is both dry and heartwarming, asking how far a person will go to maintain their isolation. -C.S.

Intermezzo (September) Sally Rooney

The arrival of Sally Rooney’s new novel is always cause for celebration. No novelist has written with such care and compassion about the early adulthood of disaffected youth in the 21st century. But in Intermezzos (Farrard, Straus and Giroux) she expands her range and moves away from the casually complex conversational tone for which she was previously known. This – don’t let it distract you! – is partly a tribute to James Joyce, in which the protagonist roams the Dublin landscape like many of his heroes. Did the Irish novelist have a message for this young female artist? If so, there’s nothing overtly offensive or political in “Intermezzo,” which might take a while to figure out if you’re expecting typical Rooney conversation, but this book rewards your effort. In another variation, the central characters here are men – a pair of brothers – rather than women, who are grappling with their father’s death and romantic relationships. One of the brothers is a serious chess player, and the game provides a framework for the entire book: How much of your life can you plan and predict, and how much is influenced by forces beyond your control? —CS

The Playground by Richard Bowles (September)

In 2018, the global success of “Tales From Above,” a brilliant novel about trees and the people who live beneath them, transformed Richard Powers’ career. Powers — who was then a respected science fiction writer — gained an aura as an ecological prophet with his vibrant and ambitious new novel, Playground (Norton) (his 14th novel), but it sank beneath the waves, becoming another warning and a love letter. The most obvious setting is Makatea in French Polynesia, a tiny atoll “lost in endless blue fields” where a tiny population must grapple with endless waste washing up on shore and a dubious consortium of investors proposing to turn their home into an island. Populated with characters ranging from a French-Canadian diving pioneer to an artificial intelligence tycoon who discovers swimming in the ocean to escape his rotting body, Playground is a fascinating depiction of an underwater universe that is as fragile as it is ancient and strong.

Die by the Sign of the Rook: A Book by Jackson Brodie, by Kate Atkinson (September)

While it certainly doesn’t hurt to have read Kate Atkinson’s five (!) previous novels, one can only applaud her latest, Doubleday, for its satirical, roguish, slightly dramatic feature. Various characters including Brodie; a young detective named Reggie Chase; the crazy Mrs. Milton; the slightly misguided country pastor Simon Cat; the lovable but sad ex-soldier Ben Jennings and a group of actors hired to spend a murder mystery weekend at Mrs. Milton’s. The grand but cash-strapped country house brings to life a story that centers on two related art thefts, but more broadly deals with loss, isolation and the sometimes blurred lines between fact and fiction. Very British hilarious, warm and funny.

Blue Sisters by Coco Mellors (September)

Coco Mellers’ explosive best-selling debut Cleopatra and Frankenstein (2022) tells a love story that begins as young as the characters involved. Her new novel, The Blue Sisters (Ballantine), continues in a similar, satisfyingly unique way, creating a world that mirrors the fates of four sisters – all addicts (to drugs, alcohol or love). The family grew up in a small, bohemian apartment in New York City and have since split up and gone their separate ways: one is a successful lawyer in London, who is slowly unraveling her lawyer life; one is a professional boxer whose career is in crisis; one is a world-famous model who has been posing since she was a teenager; and the last is a gentle and sweet teacher who recently died of a drug overdose. This complex portrait of a sisterly family is subtle and compelling, a family drama with an intimate psychological portrait.

Rejected by Tony Thulathimutte (September)

Tony Turatimut’s “Rejection” (HarperCollins) is a wonderful collection of interconnected short stories that look at ideas in the internet age through a magnifying glass. The series focuses specifically on romantic disappointment, dealing with psychological disorders, dating and identity through the eyes of Reddit users and group chat girls. Turatimut is particularly good at portraying the inexplicable errors that spiral out of control, evoking deep empathy for even his most unfortunate characters. While the posts and words look different in the digital age, he shows the eternal sting of rejection – an experience everyone can relate to. – Hua Ji

Like mother like mother (October)

Susan Rieger’s ‘Like Mother Like Mother’ tells a story that begins with a lost legacy. Lila Pereira, known as the editorial power behind The Washington Globe, was an abandoned daughter who grew up in an abusive household. She managed to escape, but she also suffered, and when she became a mother, she calmed down and stopped hurting others. This approach to child-rearing doesn’t sit well with Lila’s journalist daughter (Grace), who wants to investigate what happened to her grandmother. Despite the humble beginnings of its characters, the novel moves in and out of the upper echelons of politics and media, making it both a satisfying social milieu tale and a family drama. —Chloe Sharma

“City of Nightbirds” by Juhee Kim (November)

The world of Russian ballet is a rarefied one, and Juhya Kim’s escapist second novel “The City of Nightbirds” (HarperCollins) takes you inside St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater, past the Bolshoi Theater and onto the vast stage of the highest ballet company. King is a trained ballet dancer turned novelist, and her prose is rich, romantic and full of vivid details – the pain in dancers’ feet, the smell of sweat backstage, the burn of vodka-soaked blisters. Our heroine, Natalya, rises from simple beginnings to become a world-renowned heroine, self-confident and daring. Her story is full of drama: affairs (multiple), high-stakes competitions, and a fight in which she crashes after getting drunk. —TA

“The Contributor” by Michael Idow (November)

The ever-expanding world of spy fiction needs a Yale-educated, Visor T-shirt-wearing, millennial field agent who understands semi-autonomous machines. That’s what I thought a week after reading “The Collaborator” (Scribner), Michael Idov’s slender, tightly paced, deceptively complex novel about American and Russian intelligence. Ali Falk is a slightly jaded young agent who moves from Latvia to Poland and then Belarus and falls into an uneasy alliance with a Los Angeles actress and heiress in an attempt to solve the mystery of her missing father (and romance). Idov, who is also a screenwriter, wastes no time or words in this novel, which is as excellent as it is witty, blending together action, technology and witty dialogue. ——Tyler Antrim