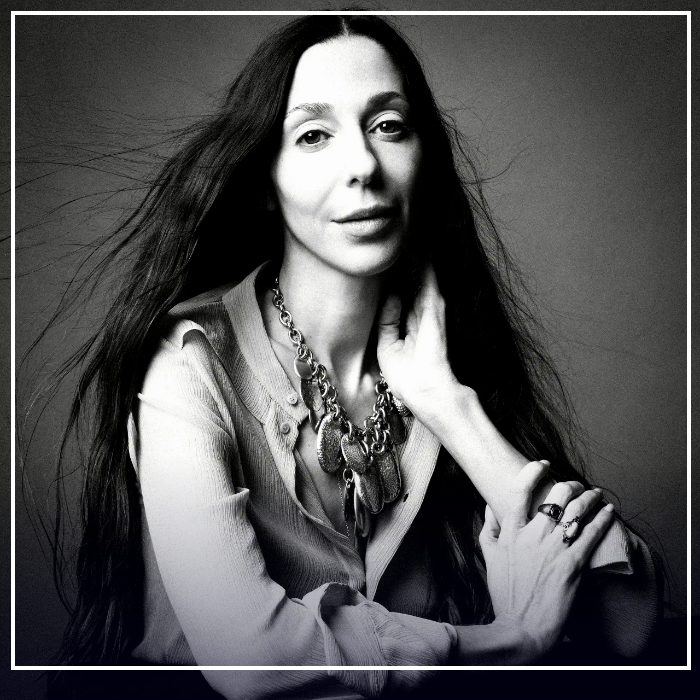

Kamali Mausam, the cup we are drinking from, with her deep eyes and Botticelli waves, talked about our walk to the store later today. She smiled often, a warm, Cheshire cat-like smile that spread across her whole face.

Kamali will replace Gabriela Hearst as Chloé’s creative director in October 2023, an appointment that comes as no surprise to those who know her and the brand. This will be Kamali’s third time working at the company, having started as an intern at age 20 when Phoebe Philo was at the helm. While the position of creative director in fashion seems to be very male-dominated at the moment, it’s no surprise that Chloé — a clothing brand made by and for women — has hired a woman for the role. While Kamali assured me she’s not the kind of leader who likes to be front and center, she also admitted that the brand’s approach and ethos fit well with her own style, which combines femininity with a casual coolness of consideration. Afterwards, I asked Chemena what Kamali would be different from her work for Chloé. (Hearst maintained her own brand while she was at the helm.) She’s skeptical of it: “I’m very conscientious about everything I do,” she says, “only about maximizing femininity.”

“That honest femininity” seemed to resonate in a surprisingly reassuring way. Kamali’s first runway show in February received one of the warmest receptions in recent years. Sheer lace blouses and flowy layers, all in soft and luscious fabrics, including spine-tingling outfits: thigh-high boots, metallic belts, leather and vinyl capes — power dressing full of undeniably feminine allure. Models walked the catwalk with their hands in their pockets and tossing loose waves to Kate Bush’s “Cloudbusting.” Music selection was helped by Kamali’s Phoenix bandmate Deck D’Arcy, as well as Kamali’s husband Konstantin Vahram, who served as Chloé’s music consultant. (As a management consultant, he helped Pfizer-BioNTech launch its vaccine during the pandemic.)

The energy in the audience was palpable, but there were also some viral moments, including a photo of front row guests (Liya Kebede, Sienna Miller, Pat Cleveland, Kiernan Shipka) with their legs crossed in parallel, each wearing the same Chloé wedges. The scene was lauded as brilliant marketing and a spontaneous casting call for the new It shoe, though Kamali told me it was completely unplanned. The RealReal is perhaps the most direct barometer of momentum, with searches for Chloé increasing 37% the day after the show and sales increasing 130% the following month.

What on earth struck such a wonderful nerve? “Fashion has always been experimental and modern, but it’s like, thank God, we can be that girl again,” Miller said. The Chloé girl, established in the brand’s early days by designers like Stella McCartney and Philo, is known for her fun, carefree (but no less important) attitude and carefree, boho-chic clothing. If you can’t be like her, you’ll want to be close to her, or at least dress like her.

Creative directors sometimes feel the need to declare their political views in their debuts — and for female designers, the pressure can be even greater. (Just before Donald Trump was elected in 2016, Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri led models wearing T-shirts that read “We should all be feminists.” In fact, Kamali has been intimately involved in sending this more subtle but equally powerful signal, dressing the former vice president twice at the Democratic National Convention, first in a cheekily titled “coconut” suit, last seen wearing a navy dress the night the candidate formally accepted the nomination.

The pieces are designed without slogans or logos but still convey a message of strength and determination. “For me, a woman wearing Chloé embodies strong femininity and confidence,” Kamali said immediately after the meeting. “Chloé isn’t transformational — wearing Chloé is about feeling like yourself.”

Kamali is a shy but strong-willed child who has been accompanying her parents to trade fairs since childhood. “She loved watching customers try things out,” said Monika. “She’s very interested in why people like or don’t like something, and she has strong opinions about what changes she would make to make it better.” Kamali has a brother, Ariane, who is an artist now living in Germany, and the four of them are very close.

When Kamali was 11, her parents moved the family to Orange County, California. The Kamali children were mired in poverty, with limited English proficiency. (“My parents said it would make them stronger,” Kamali says.) The family settled in Laguna Beach, where her parents opened another store, which Kamali likens to her German classmate Wally, a few years ahead of his time, and befriends exceptional West Coast teens. “Especially the girls are playing at a high level,” Kamali says. It was the era of Nirvana and the Smashing Pumpkins, MTV and teen magazines. Her brother started surfing, and she saw everything, “this spontaneity, this rawness — in attitude, in clothes, in music.” She spent most of her free time editing images for the international magazine Esquire Superior. She explains that she knew she wanted to be a designer before she entered high school: “I grew up in this fashion environment, but I knew I didn’t want to do that—I wanted to make clothes. Yes.”

By the time she graduated from high school, the family had returned to Germany, and she enrolled at the University of Trier to study garment construction, patternmaking, and sewing, which gave her enough self-awareness to learn how to find what she was lacking: “When you create yourself, when you have a language, your own aesthetics, your own handwriting as a designer,” she said, “you need more than that.” She met Wellum, who was studying at another university, at a party. “That look is obviously very different,” said Wellum. In one of their first conversations, Kamali told him her life plans: She was moving to Paris to become a designer. He replied, “Well, I’ll go with him.” “There are certain moments in your life when you know something special is happening,” said Wellum. The two parted ways that night without exchanging phone numbers, but reunited a few years later and began long-distance dating while Verum completed her PhD in economics.

This episode was destined to become part of Chemena Kamali’s story, as she needed to do an internship to complete her bachelor’s degree before enrolling at Central Saint Martins in London. “If you’re a German girl and want to learn about fashion, Karl Lagerfeld is your role model,” Kamali said. While many consider Lagerfeld’s work for Chanel to be his best work, his time spent at Chloé impressed Kamali. Since she was from a lesser-known German university, she suspected that her application for an internship at Chloé (then under Philo) would not receive much attention, so she went to the office in person. The receptionist turned her away, but she explained that she was taking a train straight back to Germany and asked to wait. A few hours later, she got a chance to meet the studio manager, inviting her back two weeks later; “It’s youthful recklessness,” she reflects now. “You’re not afraid – you think it’s a bit strange. But you’re not afraid to do it.”

Kamali moved into an apartment in the first district, covered in floral wallpaper, with a kitchen in a cupboard and a toilet under the shower. She remembers the Chloé studio as wild and chaotic, full of loud music and headstrong women. “I fell in love with the energy right away,” she said. She stood in front of the photocopy machine for up to 10 hours a day, copying photos of Charlotte Rampling, Lauren Hutton, Jane Birkin and Jerry Hall into mood boards. The other cadets – she was the youngest – complained, but she found it amazing to see the inspiration in person. “That was the beginning of my love for this era, because it’s not necessarily about the image of the 1970s, but mostly about the feeling,” Kamali said.

When she arrived at St. Martin’s College at the end of her internship, she was living in a tiny Victorian house in a small community in Hackney, and sleeping on long bus and Tube rides to and from campus. While some of her classmates already had their own brands and saw the master’s degree as a readjustment, she was just beginning to figure out her own brand. She studied under Professor Louise Wilson, who was known for her intelligence. (One student’s criticism of Wilson was that “it looked like a Halloween costume made by a drunk mother on a wet October night,” recalled a loving 2014 obituary. She said, “You’re so German. You’re always here. You’re always on time,” Kamali remembered. “She said, ‘I don’t want you here all week: I want you to go out clubbing.'”

The next day Kamali arrived on time as usual. The following year, as was customary, half the class was expelled and the atmosphere changed. The criticism seemed more direct: “She just wanted to squeeze everything out of you – to know your cruel heart,” Kamali says. “The fact that she was so tough on me prepared me for the industry.” After graduating, Kamali became one of the few students selected to show work at London Fashion Week. She would walk in and out of Wilson’s office up to 20 times a day, looking at models – and then return to her professor, embarrassed about why she was being so tough. “She said, ‘Never apologize for believing in the perfection of your vision: you have to think down to the smallest detail, and you have to fight for every detail because it makes a difference.’

In the months before the February show, Kamali and her team “didn’t pay attention,” she said. “It felt like we were in our own bubble and it was ours.” She recalls the attention to detail, as if she was so obsessed with her first show that she could barely sleep. The previous night, Kamali and her team were doing models’ fittings until midnight; when she got home at 1 a.m., she lay there for hours and finally gave up and got up and left the house at 5:30 a.m. Outside, in the predawn sunlight, a neighbor waved to them and wished them good luck.

Just a few days ago, my father, who had been ill for some time, passed away suddenly. Kamali said, one day she called her father and told him about her new situation and how the memory of his daughter’s ambition inspired her. “He knows,” he said. “Every struggle you face in life is huge,” Kamali said, describing the days before her first show. “To be honest, I don’t know how I did it. I think I was so shocked, my body and mind went into a weird mode and I knew he was telling me, ‘You have to do this. You have to stay focused and put in the effort and I think that helped me, karma.'” Kamali said, “It was also the toughest moment of my life.”

Since returning to Paris last fall, Kamali has settled in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a leafy neighborhood on the outskirts of the city, with Verame and their children: Vito, five, and Al, three. They moved there with some reluctance, knowing that their family was impoverished because of the California location. For a decade before leaving Paris, Kamali lived in the 9th arrondissement, where children played in a quaint square with a carousel in the middle and parents drank wine at a corner café. Her eldest son learned to walk on the wide sidewalks of Avenue Troudon, an area that became the family’s entire universe at the start of the pandemic. Kamali told me that the best bakery in Paris is Mamiche, and though the rain ruined our plans to visit their old place, we went there and bought a piece of babka.

The house is located on a quiet street in Neuilly. Inside, the wood-paneled kitchen on the first floor overlooked a walled garden, where an olive tree was hung with egg-shaped ornaments – remnants of Easter parties of long ago – and a trampoline was tucked away in a shady corner. When I arrived the day after my first session, the room was spotless, with no trace of the mess usually made by young children, except for a few colourful photographs on the kitchen noticeboard. “We cleaned up last night,” Kamali said, smiling, mimicking the frenzied antics of a mother on a mission. Although Kamali is a free spirit, she is always cautious. She led me upstairs, where Verlam – a tall, handsome, dark-haired man whose serious exterior vanished when he spoke or laughed – was working in the living room. Music played softly in the background, and Verlam later told me how important music was to both of them. Since first meeting, they have been visiting concerts and electronic music venues together in Berlin and Frankfurt, now they carefully select the games they play for their children in the car;

Kamali created a study room for herself in her home, with racks of shirts lining the walls in a rainbow of colours. It’s more like a cosy home than a workplace. Kamali has been collecting shirts for decades and estimates she now has about a thousand shirts, ranging from antique Victorian dresses to Chloé artefacts from the era of Kali and unbranded Bond shirts. The overflow was stored in the basement and at her parents’ house.

Some creative people need a broader canvas, and some people’s creativity is fueled by traditional inspiration. Kamali is firmly in the second group. “It provides a solid foundation,” she insists, “to take something from the past and turn it into something today. Though she may have had a hand in inviting bohemian fashion queen Sienna Miller to her first fashion show, she declined the term “boho chic”—the retro-inspired aesthetic of the last decade from brands like Isabel Marant and Ulla Johnson. To her it’s meaningless and doesn’t have wider historical significance.

The day before, Kamali had taken me to the flagship store on Rue Saint-Honoré, where newly painted walls gleamed and the sound of employees’ neat footsteps echoed across polished floors. Kamali said the store is a continuing testing ground for new “architectural concepts” that will reshape Chloé’s retail spaces in the coming months. From certain angles, it resembles an art gallery, its white walls hanging large colorful canvases by Danish painter Olise Kjaergaard, whom Kamali selected to be part of Chloé Arts, a new program promoting female artists. An emphasis on art and personal narrative is at the heart of Kamali’s Chloé: “It’s not just about giving female artists a platform, it’s about their stories.” (It’s a story, a little movie with a beginning, middle and end.) Kamali is more like a retail gallerist, moving less like the new mayor: warm and affable to voters but still aware of the scope of her powers.

Back in Chloé’s office a while later, she seemed to relax and led me through the archives. “I could stay here for hours,” she sighed. Underneath the sundresses and sequined blouses, numerous artifacts have been sorted by the brand’s dedicated archivist Géraldine-Julie Sommier; for example, a 1950s newspaper clipping that discussed the “hyperwoman” (called Proto) was placed beneath the power suits. Kamali reached forward for a dress, but the attendant stopped her. “I can’t break the rules,” she scolded, handing her a plastic glove. “What if someone sees me?” Next to a white crocheted mini dress, a black and white photo shows Kamali adjusting the same dress when she was still a designer. The cabinets are filled with boxes of Lagerfeld art. “He designed the most unmade clothes at Chloé,” Kamali said. Saumur added, “As few embellishments as possible. Gaby always said to him: ‘Light, light, light.'”

“Gabi” refers to Gaby Aghion, an Egyptian-born Jewish stormtrooper who founded Chloé in Paris in 1952. If Lagerfeld established the principles underlying the brand soon after taking over in 1964, Aghion established its DNA of free will. “I have to work,” Aghion told her husband the year they launched the brand. “I’m not full from lunch yet.”

Aghion’s first collection consisted of six dresses, inspired by the light sports club clothes worn by women in Alexandria, and made in the maid’s room of her apartment using simple materials usually used to cut haute couture samples. Freedom of movement is a priority. “I started Chloé because I liked the idea of haute couture, but I found it a bit outdated,” said Aghion, “The woman on the street should see beauty and quality.” Gauche Aghion has shown these dresses that women can afford.

It’s clear Kamali admires the Lagerfeld era, but she’s also a spiritual descendant of Aghion. She described attending a state dinner for German President Emmanuel Macron last spring. She was flattered by the invitation but worried about choosing a dress that was formal enough for the occasion. In the end, she wore a loose dress from Chloé’s cruise collection, optimized for modesty. “There’s nothing worse than being in an environment where you feel like you want to take something off as soon as you eat it,” she said. The weather was hot, Macron was late, and Kamali was pleased to see men in suits and women in strict dresses, “and I said, OK – not a bad choice.”

As we sat in her home office, I thought about this story. Among them is publican Chemena Kamali, who has the deciding vote on a hundred decisions every day, is a trailblazer for female-focused brands and is currently focused on her next big show. (She told me simply, “It will be similar to what she did in the first show — a palate-cleansing reset — but will also explore new territory.”)

And there’s Chemena, unsure of what to wear to a state dinner, trying to attend a yoga class or read a novel while balancing her burgeoning career with the demands and rewards of childrearing. (They both acknowledge that Varum has taken on most of the household responsibilities in recent months, and Kamali praises her cooking skills.) When I arrived, Vito and Alvar had already left for school, most of their toys put away, but I did find a special Hot Wheels tracksuit—my kids’ favorite—which proves that no matter how organized and well-organized your life is, whether it’s neon plastic or other childish necessities, encroachment is inevitable. At the end of their first show, when Kamali came out to accept their gratitude, Vito—who had been promised a tour of the aquarium if he stayed in his seat—ran up to her. He thought she was running toward him.

“There’s always a feeling of guilt,” Kamali said. “When you’re at home, you feel guilty for not doing something in the office. And when you’re at the office, you feel guilty for not being at home.” “The elusive struggle for balance,” she says, grimacing at the word – “even more challenging than the actual work.” “I feel like I’ve been preparing for this job for the last 20 years. I come in the morning and I feel like I love what I’m doing.” But the thing I find most difficult is struggling with myself. And being so tired. Kamali told me she had booked a business trip the day before – to adjust to jet lag, as well as to get away from the hustle and bustle of daily life and enjoy a good night’s sleep in a hotel room, even a good night’s sleep.

Like many of us, Kamali feels the paradox of being a woman: being willing to accept gender challenges while rejecting gender-based assumptions. When she was appointed at Chloé, the fashion house was collectively uneasy about the lack of female creative directors, and the conversation made her a little uncomfortable. “I don’t think gender should play a role,” she said. “I don’t think it should be about, okay – do we want a woman at the helm of this house, or do we want a man. It’s about talent and finding the right person for the job, in some ways.” She believes these types of conversations diminish a sense of accomplishment, regardless of gender. Still, I pressed her because I remember her telling me that her teacher at St Martins, Louise Wilson, had specifically prepared her for the difficulties women face in the fashion industry.

“Yes,” she adds, things change when you start a family: “You have to face other challenges.” However, she does not believe that women change themselves fundamentally: “You are still the same person you were before – passionate, hard-working and positive – and maybe things will get better.” It’s also a sentiment her old professor helped instill: you find someone you love, you give them your whole heart, nothing else. People can feel it. I love it too.

In this story: “To Camali: The Child” by John Nolet; makeup by Karin Westerlund. Angelina: hair, James Passis makeup, Lisa Butler. Manicurists: Camali: Sylvie Vacca; Angelina: Anatole Renée. Produced by VLM Productions.